Monique Lanoix reports on the humanitarian crisis in nursing homes.

__________________________________________

Described variously as a deathtrap, a slaughterhouse, une hétacombe, the descriptive terms used to denote the current state of nursing homes are frightening. The nurses and personal support workers who assist the residents of these homes are now called heroes. As the death toll rises, there is finally an acknowledgment that such workers are there, whatever the conditions, to care for those who are too often forgotten.

My life has been inextricably intertwined with the long-care system in Québec since my husband suffered a severe brain injury. I have watched, over the years, a system that was at best faulty progressively get worse thanks to cutbacks and a general lack of attention and support from government. Even in the public system, there has been attrition in personnel who are not properly remunerated. In the activities taking place throughout the course of a day, families help the staff meet the needs of residents, as there is barely enough staff to fully meet the needs of residents. Families are a welcomed, but invisible support. But who has heard about this in the news before the pandemic? Now the lack of staff is painfully obvious, as those family members cannot enter the homes.

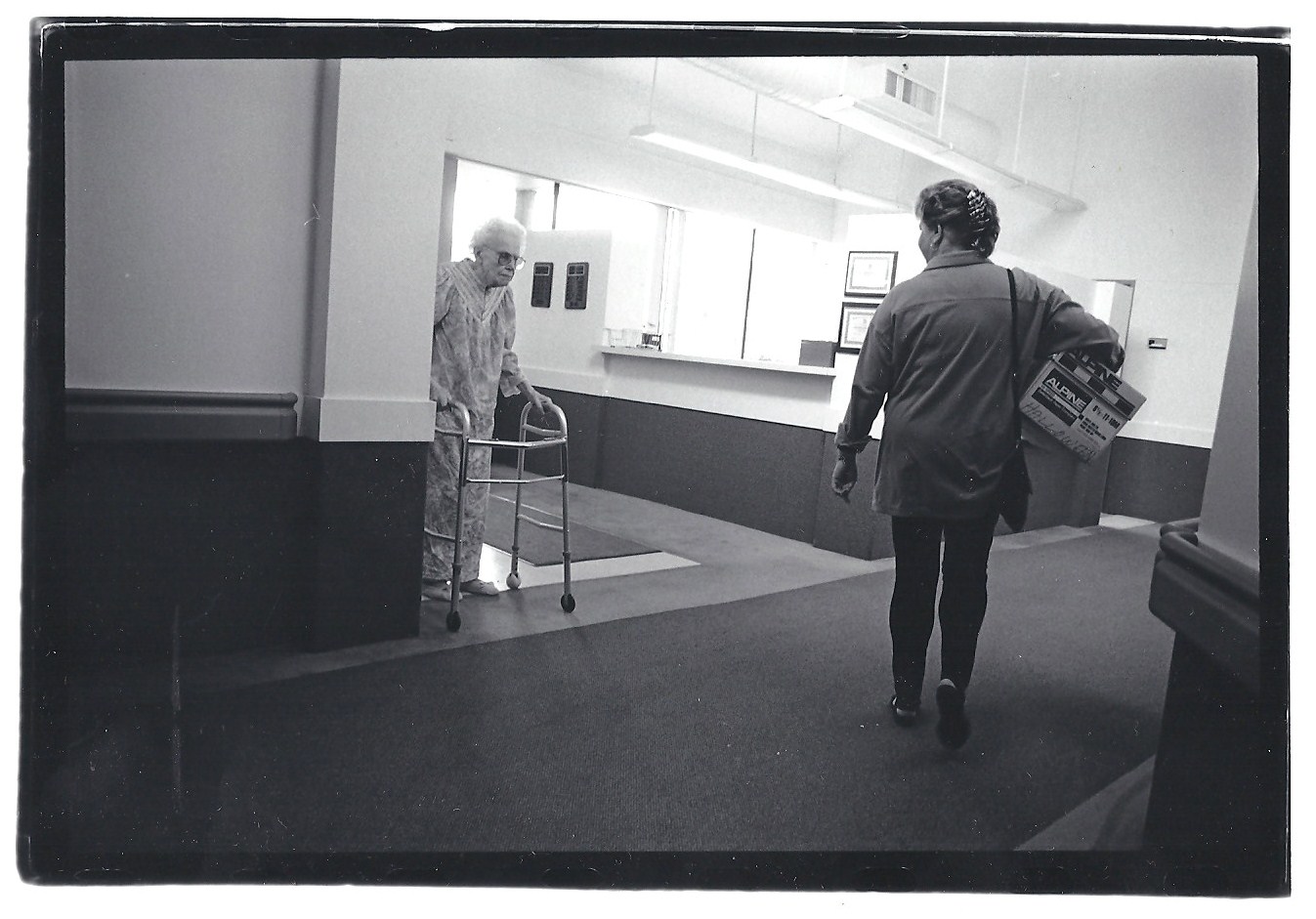

Photo Credit: Chad Gierlich. Image Description: A black and white image of an older adult woman with a visitor in a nursing home.

Since the work of a personal care worker is difficult, precarious and not well paid, there is an enduring shortage, which is worse now as workers get sick. A few days ago, Premier Legault said that he should have given personal care workers a raise. Money cannot substitute for genuine recognition, but it is a start. An in-depth look at care work and the skills such work requires is needed. Providing assistance to someone who may be frail or has dementia or some cognitive impairments requires skills, patience, and a lot of time. It is not assembly-line work. Yet our system has failed to recognize the intricacies of care work and, importantly, to value this type of work. Care work does not produce goods or fancy items; it helps someone who is in need thrive. This cannot be measured but it can be valued. We have failed to recognize this.

Like all family members, I cannot visit my husband. Nevertheless, I have tried to find out how my husband is doing. I am one of the lucky ones as I have been able to reach the nursing station of his unit. Just two weeks ago, I spoke briefly to the head nurse of the unit and she pleaded with me, “pray for us”. They did not have masks or proper protective equipment. Everyone knew a crisis was looming.

Then the tragedy of the CHSLD Herron happened. All of the sudden the Québec government realized that there was a humanitarian crisis unfolding. We think of humanitarian crises as taking place in countries that are poor or subject to war. However, it is happening and has been happening in Québec and across our country for decades now. I insist on calling it a humanitarian crisis even if it takes place in distinct centers and homes: it involves a large number of people who have been the subject of pervasive social neglect, workers and residents at the margins of society. This crisis calls for a reckoning of the way in which we treat people labelled dependent (en perte d’autonomie).

It is ironic that leaders are now saying that we must take care of “our seniors”. What do the events and this calamity say of our supposed ownership? What does it say about our concern for those who care for “our seniors”? It is clear that nursing homes are the last priority in an overburdened health system. Premier Legault spoke of a duty. I am glad that he acknowledged this care as a duty we owe to others in need and we should add a duty to care for these workers.

I am also somewhat relieved that the government has now put in measures and inspections and has provided protective gear. However, it has come far too late for many. As I am finishing this piece, I have just heard that a personal support worker has died at my husband’s CHSLD. One more person, devoted, and up until her death, invisible. It just breaks my heart to think of the people I have known over the years dying alone, even more alone than they had been. My hope is that when we, as a society, look at the horrific practices of centuries past, we take a moment to reflect on our current practices. Nursing homes, euphemistically called “God’s waiting room”, have conveniently been ignored. We need to take stock of the manner in which we have transformed this waiting room from a space of neglect into a deadly, isolated trap for those living there, and for those brave enough to confront this desolation.

In memory of Victoria Salvan and the many who have passed away.

__________________________________________

Monique Lanoix is Associate Professor in the Faculty of Philosophy and in the program in Ethics, Social Justice and Public Service at Saint Paul University in Ottawa.